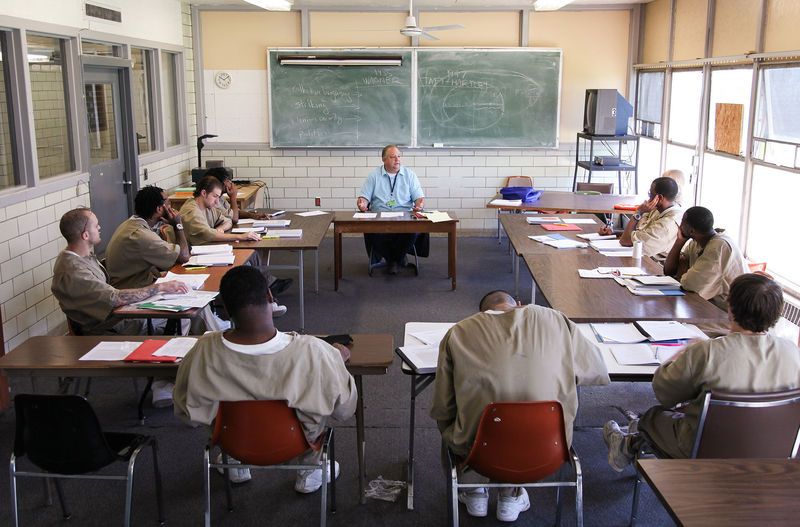

Daniel Graff, a Notre Dame history faculty member, teaches a class at the Westville Correctional Facility.

Daniel Graff, a Notre Dame history faculty member, teaches a class at the Westville Correctional Facility.

Kris remembers the moment that everything changed.

It came as he was reading The Goldfinch, the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Donna Tartt. It was the moment he discovered the true power of literature. The way it could move him, shape him, change him. The way it could ignite a spark and make him want to read more, think more, learn more.

“I thought, ‘Wow, these are just somebody’s words, but they can produce such strong feelings, emotions,’” he said. “I was fascinated by that — that language can have this effect on a person. That’s when I really wanted to start delving into it.”

That moment came as Kris was an inmate at the Westville Correctional Facility.

Mike remembers the moment that everything changed for him, too.

It came as he was reading a collection of essential American documents and reflecting on the concept of freedom. It was the moment he realized that, though he was incarcerated, his mind had been freed of the problems that led him there. And they wouldn’t be problems in his future.

“These courses helped me escape,” he said. “These help you to not be depressed. They show you there’s more to life, that this isn’t going to be forever. It gives you a way to build yourself up, to have a sense of hope.”

That moment came as Mike was an inmate taking classes taught by University of Notre Dame and Holy Cross College faculty.

The building at the Westville Correctional Facility, about 45 miles west of South Bend, where Notre Dame and Holy Cross faculty teach college-level classes for inmates.

The building at the Westville Correctional Facility, about 45 miles west of South Bend, where Notre Dame and Holy Cross faculty teach college-level classes for inmates.

Kris and Mike are two of the 37 students currently enrolled in the Westville Education Initiative(WEI), a program that allows select inmates to pursue Holy Cross associate and bachelor’s degrees in liberal studies that will accelerate their eventual re-entry into society.

Driven by a commitment to Catholic social teaching and a strong belief that a liberal arts education can transform lives, WEI has allowed nearly 100 inmates to receive college credit since 2013. Four have earned AA degrees, and seven more will graduate with one this month.

Of the 15 WEI students who have left prison, none have re-entered the correctional system.

Developing a strong foundation in reading, writing, research, public speaking, and critical thinking offers benefits that go far beyond the professional opportunities a degree might one day provide.

“Having the power of complex thought changes the way that people can exist in the world,” said Kate Marshall, a Notre Dame associate professor of English and member of the WEI faculty steering committee. “It changes the way a person relates to a community, the way a person relates to a culture. The liberal arts education provides a model for being in the world.”

“Having the power of complex thought changes the way that people can exist in the world. The liberal arts education provides a model for being in the world.”

— Kate Marshall, associate professor of English

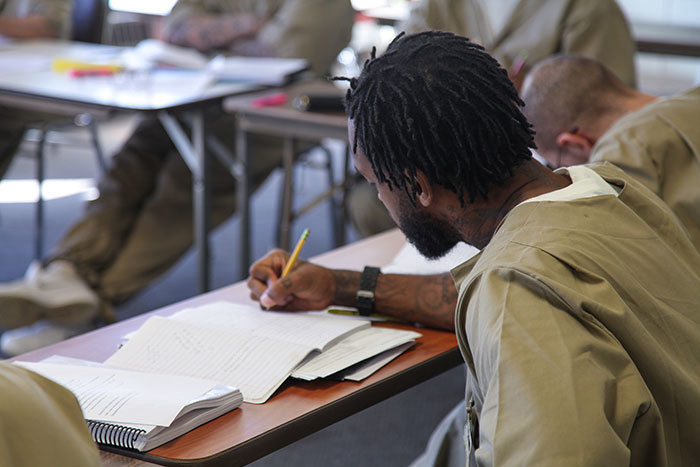

Westville students discuss a reading during class.

Westville students discuss a reading during class.

A Community of Scholars

It’s a Tuesday afternoon in February, and Gabriel Said Reynolds is leading a class through a close reading of Christian and Islamic texts.

Reynolds, a Notre Dame professor of Islamic studies and theology, frequently guides such conversations in his introductory courses for undergraduates in South Bend. This class, however, looks much different.

The students are all clad in tan jumpsuits. They carry their materials in mesh bags. Their age range spans at least two decades. Half are Christian, half are Muslim.

Once class begins, however, the differences fall away. As Reynolds helps them analyze the assigned texts — today, it’s passages from C.S. Lewis, Thomas Aquinas, the medieval Muslim writer Al-Ghazali, the Bible, and the Quran — the conversation immediately resembles one found in any humanities seminar on the Notre Dame campus.

“They’re really interested and extremely invested in the course,” Reynolds said. “They do the reading, they’re active in class, they ask a lot of questions. It’s also challenging for them, because these are not abstract questions of interpreting a text in an academic way. These are very important topics to them at a personal level.”

For WEI’s founders, creating a thriving intellectual community through intense collegiate coursework has been the goal from day one. Nearly five years ago, a group of Notre Dame and Holy Cross faculty and administrators began exploring the possibility of such a program and developed a relationship with the Bard Prison Initiative, a robust prison education system established in 1999 by Bard College in New York.

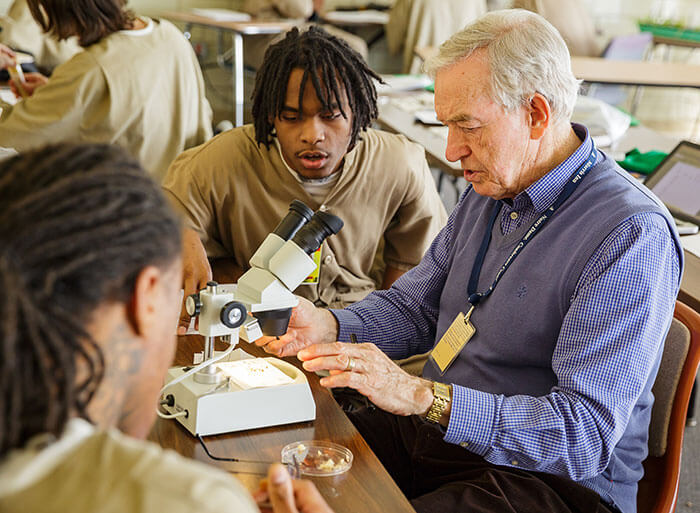

In 2013, the program launched at Westville, an all-male prison about 45 miles west of South Bend, with a handful of classes and 20 students enrolled. Now, the program has grown to more than a dozen classes per semester — offerings in science, math, and composition as well as humanities and social science seminars such as the History of Medicine, Labor & America to 1945, and Christ, Church & Culture.

WEI has offered humanities and social science seminars such as American Politics: Promise & Reality, Great Comedies, and Introduction to Philosophy.

WEI has offered humanities and social science seminars such as American Politics: Promise & Reality, Great Comedies, and Introduction to Philosophy.

The admissions process is rigorous — 150 inmates from Westville and the Miami (Ind.) Correctional Facility took the entrance essay exam last year, about 70 were selected for personal interviews with members of WEI’s faculty steering committee, and 32 were ultimately admitted to the program.

“We are looking for great potential,” said Alesha Seroczynski, WEI’s director of college operations. “Many applicants did not complete a high school diploma and often earned their GEDs in prison. This is not about doing well on a standardized test or having an excellent high school transcript. We want men who are great thinkers, good writers, and have the potential to be outstanding college students.”

That goal has manifested in men like Ali, a promising student who administrators hope might one day be the first WEI alumnus to enter graduate school.

This semester, he’s in Reynolds’ Islam & Christianity class, as well as the History of Enlightenment and Composition II. He now counts Crime and Punishment and the 18th-century French novel Dangerous Liaisons among his favorite books. Though he entered the program hoping to one day become a writer, he’s thinking bigger now, dreaming of working for a foreign aid organization tackling global issues.

“Through this process, I’ve learned to analyze the world through a different lens,” he said. “The world’s problems aren’t as black and white as we like to think. There’s gray area, and that’s where I’m trying to live. I want to make that gray area colorful.”

“We want men who are great thinkers, good writers, and have the potential to be outstanding college students.”

— Alesha Seroczynski, WEI director of college operations

A Culture of Engagement

Stephen Fallon remembers the moment that changed everything.

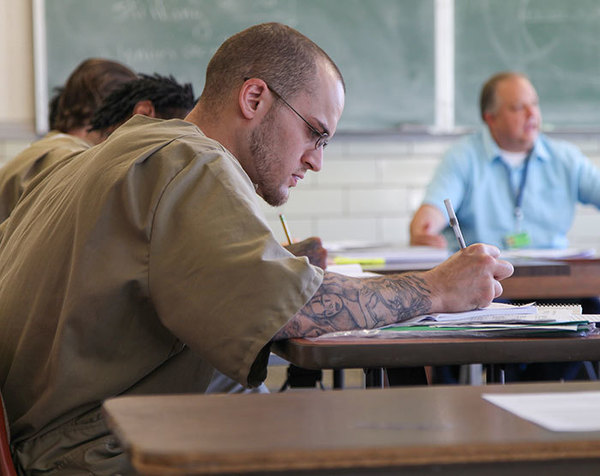

Fallon, the Rev. John J. Cavanaugh, C.S.C., Professor of the Humanities in the Program of Liberal Studies and the Department of English, was handing back the midterm exams in his Shakespeare & Milton course.

He usually offers the upper-level class at Notre Dame, but Fallon had similarly high expectations of his Westville students — careful reading of the texts, engagement in class discussion, thoughtful responses to writing assignments.

In the first half of the semester, one student had been quiet, seemingly disengaged from the material or failing to comprehend it. But seeing Fallon’s response to his essay exam — learning that his ideas had impressed his professor — was a moment of transformation.

“He looked at how well he had done, and you could see in his face that he was surprised,” said Fallon, a member of the group that founded and developed WEI. “He realized he had thoughts of value, that he had done something interesting with the text, that he understood it. That was priceless to me.”

The WEI curriculum also includes coursework in math and science.

The WEI curriculum also includes coursework in math and science.

Growing confidence among a growing number of students has, in turn, helped grow the community of scholars at Westville. Classroom debates over philosophical, theological, and sociological topics often carry over into the wing of the dormitory-style unit the students live in.

While WEI students currently share living space with inmates not in the program, administrators hope to eventually have a building comprised entirely of WEI students — further enhancing the effort to form an academically focused environment.

Like many faculty members teaching classes at Westville, Marshall was impressed by how quickly students embraced the material they were given. She taught a Novels of American Naturalism class in the program’s second-ever semester, assigning realist fiction including Cormac McCarthy’s The Roadand Frank Norris’ McTeague, and she assisted in leading a Modernism seminar last semester.

“What’s remarkable about teaching in this program is the way the space of the institution is transformed so rapidly,” she said. “When you teach these classes, you’re not completely unaware of the context, but the context falls away when you’re engaged in an intellectual project. I was surprised how quickly that kind of serious collegiate atmosphere was achieved.”

“Our role is to give people some hope, give them a chance, let them have a flicker of intuition and insight. If you just kindle that little spark, it can carry people a really long way.”

— William Carbonaro, associate professor of sociology

The environment is not without its challenges. When the program began, students had no access to computers, writing all assignments by hand. They now have limited time each week to use computers to type essays and papers. With no Internet access, their research capabilities are limited to the gradually growing WEI library and materials they request from professors or graduate student tutors.

Nevertheless, the students produce impressive work — one research-based presentation on Native Sonand narrative irony, Marshall said, was among the most extraordinary she had ever seen from an undergraduate.

Improving the quality of students’ writing, Fallon said, continues to be a key point of focus for the program. Graduate students and a post-doctoral fellow work with students on their writing, and plans are developing to offer further opportunities for tutoring and training services.

Just as faculty members would know nothing about a Notre Dame student’s background, the professors and administrators avoid knowledge of WEI students’ personal history, learning only what comes out in class discussion.

“Most people at Westville are not going to spend their entire lives there,” said William Carbonaro, an associate professor of sociology who taught a course on U.S. social inequality. “We can talk about how and why they got there, but the more pressing thing as a society is what happens to them once they leave. To me, our role is to give people some hope, give them a chance, let them have a flicker of intuition and insight.

“It seems like it might be a small thing, but if you just kindle that little spark, it can carry people a really long way.”

Alesha Seroczynski, WEI’s director of college operations, working with students in the computer lab.

Alesha Seroczynski, WEI’s director of college operations, working with students in the computer lab.

A Future of Opportunity

Kris and Mike are waiting for another moment that will change everything.

Both men are set to be released this year and will be looking to take their next intellectual step. Kris earned his associate degree prior to starting at WEI; Mike will earn his in May. They’re hoping to add their names to the list of WEI students who have applied for transfer to other schools, including Holy Cross, Ball State University, Indiana University South Bend, Purdue University Calumet, and Wabash College.

Since entering the Westville program, Kris’ passion for reading and writing has rapidly accelerated. He loves coming-of-age novels and takes mental notes on style and structure as he reads, applying observations about what he does and doesn’t like to his own writing. His paper analyzing how the Chris Abani novel GraceLand, set in the slums of Nigeria, functioned as a metaphor for the nation as a whole remains a major point of pride.

And the chance to engage with his peers and Notre Dame professors on works like Paradise Lost or King Lear has sharpened his critical-thinking ability, which he knows will be essential once he walks past Westville’s walls.

“You can apply that to any obstacle that comes your way,” he said. “At work, at school, or in my personal life, now I know anger is not the best route. I just need to slow down, take a few minutes, think about it, and make the best decision I possibly can.”

I’ve come to find out who I am and what I stand for and what I believe in. I’ve learned that I’m a pretty strong guy, and I can overcome a lot of difficulties.

— Mike, Westville Education Initiative student

For Mike, his Westville education has been a chance to hit the reset button. As a college freshman, he studied journalism, and he hopes to return to that track soon, perhaps one day covering sports or writing a book about his life experiences.

In a course on Inequality in American Education — taught by Maria McKenna, senior associate director of Notre Dame’s education, schooling, and society minor — he spent several weeks researching disadvantages facing students with attention and behavioral issues. That and other experiences in WEIclasses have helped reform the way he thinks about the world — and the way he thinks about himself.

As of this month, 11 WEI students will have earned AA degrees, and several have applied for transfer to schools such as Indiana University South Bend, Ball State University, and Purdue University Calumet.

As of this month, 11 WEI students will have earned AA degrees, and several have applied for transfer to schools such as Indiana University South Bend, Ball State University, and Purdue University Calumet.

“I’ve come to find out who I am and what I stand for and what I believe in,” Mike said. “I’m able to put those principles into my everyday life. That’s something I wasn’t doing before I got locked up. I’ve learned that I’m a pretty strong guy, and I can overcome a lot of difficulties. This experience has allowed me to get my mind right and really focus on what I want to do.”

WEI’s leadership team — which includes Seroczynski; Fallon; Marshall; Jay Caponigro, Notre Dame’s director of community engagement; Christopher Kolda, chair of the Department of Physics; Richard Pierce, an associate professor of history; and Brother Jesus Alonso, C.S.C., Holy Cross’ vice president for strategic initiatives — are also optimistic about the future. By 2019, they hope to have 100 students enrolled simultaneously, and anxiously await the day when the first WEI student completes the requirements for a Holy Cross bachelor’s degree.

This education, they know, will allow WEI students to return to society as avid learners, clear writers, and bright thinkers.

It will have changed everything.

“I want them to become sensitive and thoughtful participants in their own lives. I want them to avoid becoming easy prey to easy answers,” Fallon said. “I want them to be better advocates for themselves. I want them to get the tools that a liberal arts education can give a person. This will prepare them to do anything.”

“I want them to become sensitive and thoughtful participants in their own lives. I want them to avoid becoming easy prey to easy answers.”

— Stephen Fallon, the Rev. John J. Cavanaugh, C.S.C., Professor of the Humanities

A Reflection on Pratice

In a related piece published this summer by Notre Dame Magazine, Maria McKenna, an associate professor of the practice for Africana Studies reflects on her experience as an instructor in the WEI program:

Indiana’s Westville Correctional Facility, a repurposed mental institution, looks as though time stopped in the mid-1950s. Where the walls are not bare, they are adorned with sexual-assault reporting protocols, rules framed neatly and affixed to the cinderblock, and the occasional random poster from about 1982. I wonder what a bleak space like this does to the souls of the people confined here day after day.

The halls of the prison buildings smell of antiseptic cleaning supplies used daily by young men whose job it is to mop over and over again, even when nothing needs mopping. Chipping paint, plastic-wrapped broken windows and varying degrees of disrepair are everywhere. The constant clicking of security gates and the incessant walkie-talkie communication are forever drilled into my memory. Omnipresent lines of men come and go from one space to another, the green and orange sock caps on their heads providing the only color against the wintry gray background.

Largely unused basketball hoops, outside pay phones and dusty courtyards with high fences and barbed wire remind me that the lives of those incarcerated here are not their own. The never-changing daily lunch menu makes me think that when they leave this place, if they ever do, the men will never again eat a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.Although it is called a “correctional facility,” rehabilitation here seems to be an afterthought — perhaps out of necessity. The well-meaning prison employees I encountered had such specific job descriptions, working, for example, as gate guards or unit supervisors, that bringing change to the system was clearly outside the scope of their day-to-day responsibilities.

When I agreed to teach in the Westville Education Initiative, which began in 2013 when Notre Dame and Holy Cross College joined Bard College’s Consortium for the Liberal Arts in Prison, I admit that I was scared. Scared I didn’t have enough command of a classroom to absorb individuals whom I presumed to be tough and difficult to reach. Scared to engage with people I perceived as vulnerable and needy. Scared about how gender would play out in the classroom.

One of the administrators of the program gently admonished me at the start of the semester: “Remember your job is to teach your class and teach it well. It’s not to change the prison system nor is it to save anyone.” It was sage advice, but I couldn’t help but wonder about my larger responsibility to challenge issues related to our criminal justice system and mass incarceration.

After the security clearance, mandatory self-defense training and the “shakedown” process to enter the prison, I anticipated that my first class session would be something more than merely meeting a new group of students. I was encountering incarcerated men. The system didn’t let me forget that. The process seemed designed, in fact, to be a constant reminder.

Then I met my students. On the very first day, in an assignment prepared ahead of time, members of the small group were to deliver to the class, from memory, a piece of a famous sermon by Martin Luther King Jr., in the cadence and style of a Baptist preacher. I should mention that I’m a white woman who works in the Department of Africana Studies and the Institute of Educational Initiatives at Notre Dame, in this case teaching men of all ages and ethnic and racial backgrounds about the different ways people of color have been, and continue to be, marginalized in the U.S. educational system. It’s a loaded course with controversial material, demanding a certain level of trust to engage in fully.

I walked in, introduced myself to the students, called them all by their last names, as prison protocol suggested I do, and began class. I was reminded by a nagging voice some of us would think of as our conscience to be impressed with the fact that, despite these students having just met me and having no reason at all to trust me yet, almost everyone was prepared to do what I asked. There was a quiver in some of their voices as they began, and vocal skepticism as I made them climb on top of a chair to deliver their address, but they did it.

In that moment, listening to them deliver their speeches, I realized how unfair it was for me to come in with preconceptions of how “these students” were going to be. I realized how unfair it was for me to worry that I wasn’t enough of an educator to teach what I know so well and love. And I realized how unfair it was for me to doubt that I would connect with these students in the same ways I’ve connected with students since the beginning of my teaching career.

It reminded me that I had an obligation to treat these students the same way I do any others I teach. I could no longer look at these men as “students who are also incarcerated,” nor was it my job to proselytize about second chances or the “opportunity” this represented for them. For the sake of all of us, they needed to be just students. I know now that this was the least I could offer them, given the trust they displayed in me that first day.

Over the next few weeks we read all different types of literature and research, including the work of Anna J. Cooper and W.E.B Du Bois, trying to unpack what it means to learn, to know something deeply while drawing on lived experiences. We learned together about African American, Mexican American, Asian American and indigenous peoples who bravely challenged inequities in education throughout U.S. history. Along the way, we used writing, diagrams, note-taking, discussions, debates and drawings to tease out our ideas. I was no longer “just” the instructor and they were no longer “just” the students. The students and I became a “we.”

At some point, I started using their first names, and I was reminded of the writer Linda Christensen’s article, “To Say the Name Is to Begin the Story.”

From then on, we were engaged in the time-honored tradition of using every available piece of knowledge and experience to make sense of ideas. And the class became personal, because real learning is always personal. The students worked to reflect on and make sense of their own educational background. They learned to trust that even though their experiences were different from someone else’s in the class, they were equally valid. We came to appreciate that there are multiple ways to experience the same thing and multiple meanings of important ideas.

My work within the prison walls of Westville is a reminder of the magical opportunity of teaching. Beautiful learning comes in lots of shapes, forms and spaces. It comes in the chiseled face of the tattooed young man eager to explain his upbringing to his classmates. It comes in the slouched weariness of an understandably cynical student who gradually comes to life over the course of the semester as he realizes his ideas matter to the conversation. It comes in the gentle, uncertain voice that asks, “Do you know what I mean?” after everything he adds to the conversation. It comes in testimonies of educational plans gone awry and graduation speeches that give us a glimpse of a student’s former life. It comes in the bravery of the student who speaks up for the first time in the last few weeks of class. And it comes in the impassioned plea of one student to the others to take their education seriously.

In the end, the students I had the honor of encountering at Westville taught me that even with the gray cast to the buildings, the clanging of the locks and the suffocating antiseptic smell, human dignity can endure in even in the bleakest circumstances, and that we have a collective obligation to support all children, families and communities in meaningful and caring ways.

Originally published by Josh Weinhold at al.nd.edu on August 13, 2016.